[ad_1]

On a warm evening in late August, Harley received bad news at the Dolores Shelter Program, a site in the Mission for adults experiencing homelessness: There were no walk-up beds available that night.

When another man said a case worker told him the site offered walk-up beds, a shelter employee responded: “I don’t know why they do that. They send you in circles.”

More people toting backpacks and suitcases milled about on the sidewalk beyond the teal metal bars that separated them from a hot meal and bed for the night.

When Harley, who didn’t share his last name, got into a motorcycle accident and lost his job, he also lost stable housing. He said he called San Francisco’s Homeless Outreach Team’s voicemail three times that week asking for help getting into a shelter, but that his calls went unreturned.

Many elected officials, including Mayor London Breed, have said that large numbers of people experiencing homelessness are not interested in what resources the city has to offer, citing data from the Healthy Streets Operation Center.

But new records requested from the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing and interviews with housing providers show that it is difficult for people seeking shelter to obtain it due to a shortage of beds and other barriers they encounter trying to access city services.

From late January 2023 to early August 2023, people left messages in the Homeless Outreach Team’s voicemail system more than 2,000 times requesting shelter, and 68% of those requests were “unable to be fulfilled,” a Public Press investigation found. In most cases, this means that the city was unable to connect with the caller in person or on the phone — because there was not enough information to locate the person, the person did not respond to callbacks, the person’s voicemail box was full or the number was disconnected, or the dispatch team could not find them at a specified location. In few instances, the city was in contact with the person but did not have any shelter beds available to offer the caller.

In that same time period, only 56 offers of shelter were rejected by those seeking shelter — a mere 2.7% — while the city provided shelter for 110 people who requested a bed. In 243 instances, city employees did not record an outcome. Another 240 requests were marked “not applicable,” for a variety of reasons: the request was not clear, the person no longer needed help, they did not live in San Francisco, or the call came from a concerned citizen or provider. There are not enough resources to respond to calls from people who are not experiencing homelessness themselves, city employees said.

Discussing how the city handles requests through the hotline’s voicemail — there is no option to speak to a live person — employees said that many people do not want the shelter options offered, and that connecting with callers is tricky because many of them do not have reliable access to phones or do not stay in one spot until city staffers arrive, sometimes days later.

Interviews with employees at five organizations that provide shelter and run coordinated entry sites that assess people for housing referrals were consistent: There is high shelter demand in San Francisco and often not enough supply.

“Providers working with the unhoused are pretty screwed right now,” said Colleen Murakami, Chief Development Officer at Swords to Plowshares, an organization that serves veterans. Housing veterans is challenging as there are no longer shelter beds set aside for veterans and treatment beds are scarce, forcing the organization to rely on private funds to get veterans off the street as they await permanent placements, she said.

Providers for families and transitional-aged youth also cited problems with lack of resources.

“We are assessing families from the moment our doors open to the moment they close,” said Hope Kamer, director of public policy and external affairs at Compass Family Services, a nonprofit that runs a coordinated entry access point for families. “It’s an unending tide of need.”

San Francisco is in the midst of a highly publicized lawsuit brought by several unhoused people and the Coalition on Homelessness against the city for failing to offer shelter during sweeps, not following its own encampment clearing policies, and seizing or destroying people’s possessions. Because the city does not have enough shelter beds for its unhoused population, plaintiffs argue that clearing tent and vehicle encampments without offering viable housing options is cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment.

In December 2022, U.S. Magistrate Judge Donna Ryu issued a preliminary injunction preventing the city from citing, arresting or threatening people involuntarily experiencing homelessness to clear encampments. The lawsuit has sparked heated debates across the city, with the mayor, several members of the board of supervisors and Gov. Gavin Newsom decrying the action for limiting the city’s ability to address homelessness on its streets.

The definition of the term “involuntarily homeless” has become a key issue in the lawsuit.

Following clarification at a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals hearing, Breed announced on Sept. 25 that the city will resume sweeping encampments where people are “voluntarily homeless” — the term that the parties to lawsuit are using to describe those who refuse shelter or who are sleeping on the streets despite having a shelter bed elsewhere.

Lack of shelter beds

San Francisco last measured its unhoused population in August 2022, recording 7,754 people experiencing homelessness. However, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s website notes that the annual census is likely an undercount, estimating that San Francisco could have as many as 20,000 people who experience homelessness annually.

Elected officials acknowledge the shortage of shelter beds, with Breed’s most recent budget recommending the addition of nearly 600 beds, and at least one supervisor, Rafael Mandelman, requesting even more. Breed’s proposed additions would bring the total number of temporary beds available to about 3,700, which would accommodate less than half of the unhoused people tracked in the 2022 homelessness count.

On the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing’s shelter dashboard, occupancy usually hovers around 90%, though written explanations from the department note that figures are not a true reflection of the city’s capacity at a given moment. Many beds are reserved for certain programs or teams carrying out daily operations, and thus may remain vacant.

“They love showing vacant beds,” said Jennifer Friedenbach, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness. “Because for political reasons, it feeds into the mythology that they’re always trying to create that homeless people are there by choice.”

Friedenbach said that before the pandemic, the city had a one-night system through which adults could wait in line at drop-in centers around the city to try to secure a vacant bed at one of several shelters for the night. Today, the city offers only one walk-up shelter for adults, and spots there are hard to come by.

For families and pregnant people seeking shelter, the city has been piloting emergency hotel vouchers in partnership with Compass Family Services. But Kamer estimated there were still about 60 families in the family shelter queue as of late August.

Youth homelessness in San Francisco has decreased over the past 10 years as housing investments for young people increased, but “we still don’t have sufficient resources across for all of the young people that are experiencing homelessness on any given night, or throughout the year,” said Sherilyn Adams, executive director of Larkin Street Youth Services.

The gap in services is particularly pronounced for people between ages 18 and 24, said Katie Reisinger, director of health and safety at Huckleberry Youth Programs. While it is rare for both of the city’s two shelters for adolescents between 12 and 17 to be at capacity, there is almost no housing for 18-year-olds who age out of those programs, Reisinger said.

Missed connections and other barriers

The Department of Homelessness offered several explanations as to why so many voicemail requests were unable to be completed. Requests must come from people in San Francisco — if they say they are calling from another city, the department will not respond to their request for help. In many cases, people seeking help do not have their own phones and they use a stranger’s, so callbacks from the outreach team go unreturned. In other cases, those who call don’t leave adequate descriptions of their location or themselves, or when the Homeless Outreach Team shows up to a specified location, the caller is no longer there.

The team will attempt to locate an individual three times before stopping the search, said Brenda Meskan, an operations coordinator with the San Francisco Homeless Outreach Team.

There are a variety of other pathways people can use to seek temporary shelter in San Francisco, and for many of them, having regular access to a phone or the internet is often key to the process, which relies on people signing up for online waitlists, contacting various nonprofits or making appointments at one of the city’s coordinated entry access points.

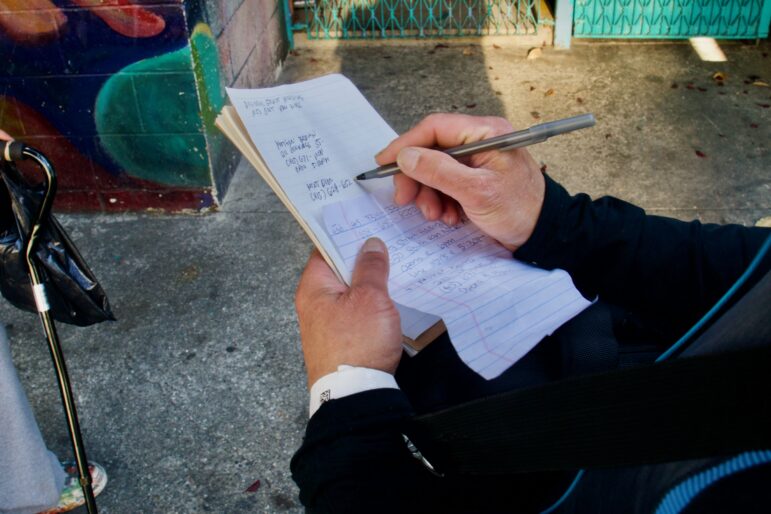

Madison Alvarado / San Francisco Public Press

People experiencing homelessness often rely on word of mouth to learn about shelter access, sharing knowledge with one another and keeping track of information with pen and paper.

Many people turn to the Department of Homeless and Supportive Housing’s website for information about how to access shelter. Deborah Bouck, a communications manager for the department, said updating the website is a priority because people seeking shelter rely so heavily on it. However, in at least two recent instances, information on the site regarding coordinated entry access points was listed incorrectly. It was updated in early September following inquiries from the Public Press regarding discrepancies between the website and information provided by nonprofits running access points.

Bouck said that providers are responsible for notifying the department about changes in their hours or access procedures so the site can be updated, and that the department meets with groups every two weeks, providing regular opportunities for conveying new information.

Service providers noted other challenges that make it difficult to help certain growing populations, such as transitional-aged youth who have children, placing them on the family track, which isn’t designed to cater to young people. Kamer also pointed to families with children who are too young to be in school, preventing them from qualifying for otherwise appropriate shelters, such as the Buena Vista Horace Mann Stay-Over Program.

New shelter waitlist

In recent months, advocates criticized the hotline as an ineffective way to connect people with shelter sites and pushed for a return to the online waitlist that the city had in place before the COVID-19 pandemic.

The city listened. On July 5, San Francisco launched the new waitlist. In just over five weeks, almost 700 people had signed up, but 121 did not respond when they were offered beds, meaning their names were later removed from the list. The city reported 19 request cancellations. As of Sept. 20, there were 484 people waiting for spots to open up, while the city had placed 113 people.

“Since the pandemic, we have been striving to streamline access to shelter, while also ensuring those living on our streets access the care and services they need,” Denny Machuca-Grebe, a former spokesperson for the department, wrote in an August email when he was still working for the department.

Advocates say that the new waitlist is an improvement, but note that the options available are more limited compared with those available via the pre-pandemic waitlist. Current options are limited to congregate living — with many people who don’t know each other sleeping in the same room — which is not a viable option for everyone experiencing homelessness, especially those who have post-traumatic stress disorder, experiences with severe trauma and other disabilities. Congregate shelters for adults can also feel unsafe to transitional aged-youth, said Adams of Larkin Youth Services. The city’s Frequently Asked Question site for the waitlist notes that only individuals who can get in and out of a bunk bed unassisted should register for the waitlist.

Other requests for help

Will McKennett, a brain cancer survivor and employee at the San Francisco Zoo with a passion for reptiles, knows the difficulty of finding shelter. In late August, McKennett said he had shown up at the Dolores Shelter Program hoping to find housing on several nights with no luck.

“It’s tough,” said McKennett, who has been homeless since last year when he was evicted for smoking too close to doors and windows. He was recently cut off from social security benefits after the administration discovered it was mistakenly overpaying him and demanded that he repay $14,000. “But why is that my fault?” he asked.

Though the Homeless Outreach Team was able to help him secure a spot in a navigation center, McKennett was kicked out for reasons he did not share. The congregate shelter was not ideal for him, as many other people in the center were using drugs in the bathroom or didn’t take the coronavirus pandemic seriously, he said.

Without a shelter bed, McKennett sleeps outside or in a chair at the United Council of Human Services between paychecks. Once the money comes in, he spends $300 on a hotel each week until his funds run out, he said.

While requests for shelter comprise the majority of calls to the Homeless Outreach Team’s hotline, nearly one-tenth of callers were interested in speaking directly with a member of the team (in person or on the phone), and another tenth simply wanted information.

Of the 3,584 calls to the team from late January to early August, data shows that the city returned 364 requests for outreach, assessed 105 people for coordinated entry, and gave 522 people referrals for case management or shared other information, such as details about the city’s housing and shelter programs.

“We consider any connection with clients to be a success,” Machuca-Grebe wrote in response to questions regarding how the city measures the hotline’s success in connecting individuals to shelter.

McKennett said that in his experience, the Homeless Outreach Team is great about bringing blankets to people on the street. In the meantime, he was still searching for a permanent place to call home.

Correction, Sept. 29: This post was edited to update a quote attributed to Swords to Plowshares about shelter availability that the organization said was missing context.