[ad_1]

This article is adapted from an episode of our podcast “Civic.” Click the audio player below to hear the full story.

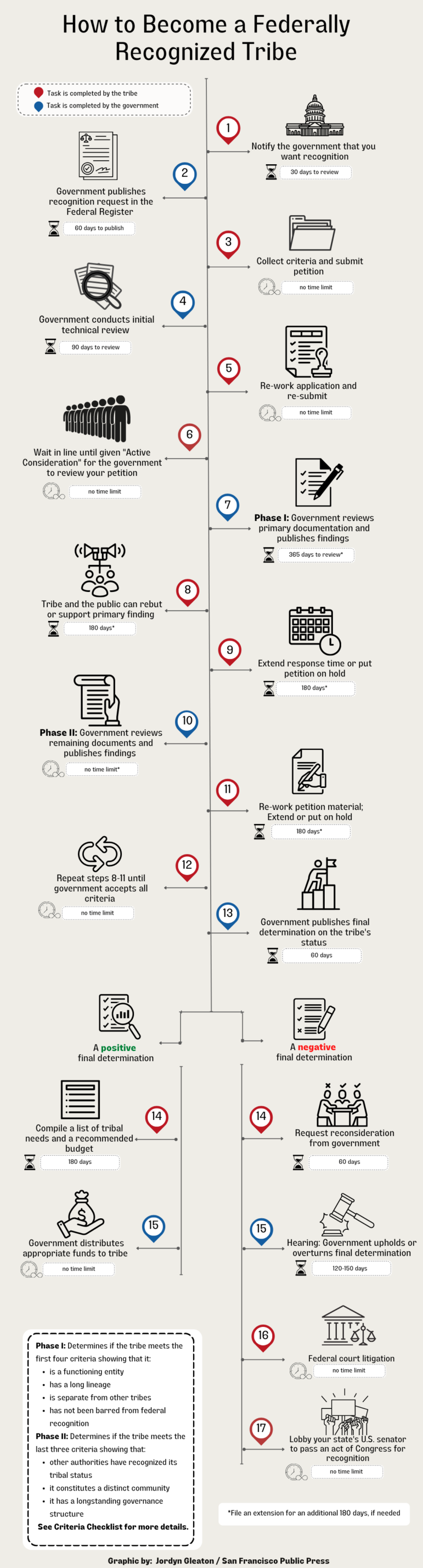

In 1978, the U.S. government created a path to recognizing Indian tribes in the United States. Four years later, the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation, a tribe native to Yosemite Valley, submitted its initial request to become a recognized tribe.

The tribe is still waiting.

Obtaining federal recognition is often seen as the “golden ticket,” because it allows tribes to organize collectively and access federal resources. Recognized tribes can get funds for housing or climate resilience, for example. They also can establish sovereign governmental status, giving them authority to collect taxes and administer laws.

“It means that tribes have the ability to take care of their community members through health, through education and through other services that the government promised us when they stole our land hundreds of years ago and continue to steal our land now,” said Cristina Azocar, an Indigenous journalist and professor at San Francisco State University.

California has the highest Native American population in the country and is also home to the majority of non-federally recognized tribes. The Death Valley TimbiSha Shoshone Band is the only California tribe that has been recognized in the 44 years since the federal acknowledgement process was established.

In the last 13 years, the U.S. Department of Interior has actively reviewed applications for acknowledgement of only 18 tribes, even as hundreds remain in line. The Public Press has identified more than 400 tribes seeking federal recognition and is working to confirm that 200 others with publicly listed applications are genuine. Many have been waiting for decades.

A Public Press request for expedited release of records listing all non-federally recognized tribes was denied by the Department of the Interior, as was an appeal of that denial. No timeline has been given for their release.

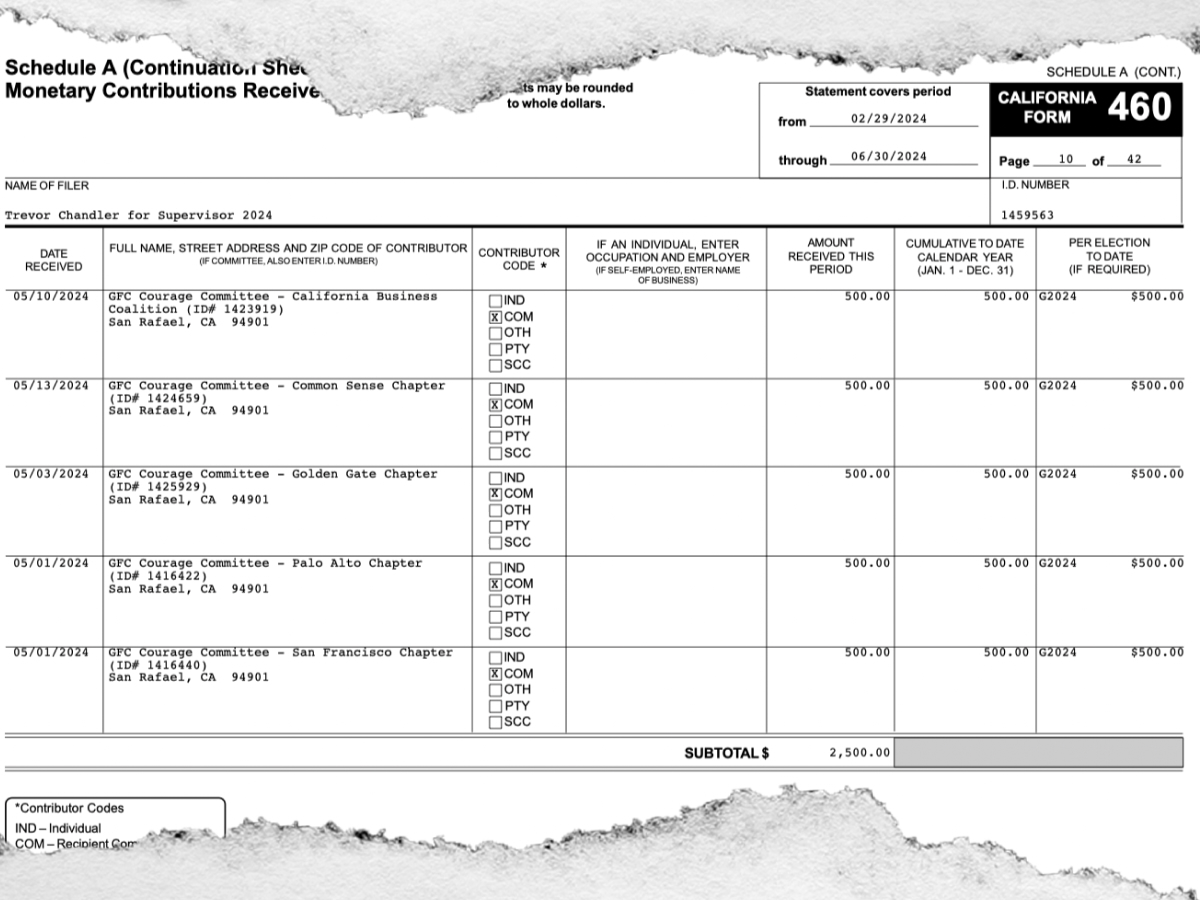

The application process is long, complex and stringent. While the government gives tribes tight deadlines to submit documentation, it allows itself unlimited time to review materials after its initial assessment. On top of that, the COVID-19 pandemic has contributed to a slowdown in processing.

“Especially during COVID, tribes that had federal recognition were much more able to take care of their people than tribes without federal recognition,” Azocar said. “My own tribe, we were sent tests, we were sent masks.”

Federal recognition also gives tribes access to emergency funding from sources like the $2.2 trillion in COVID stimulus funding provided by the Cares Act, federally funded health care and education, the right to operate casinos, and the ability to convert their land into housing.

A rigorous process

The federal acknowledgement process set up in 1978 is the main path tribes take to become recognized and listed in the National Registry, an annually updated reference list. As of this year, there are 574 recognized tribes, most of which received their designation through treaties, acts of Congress, executive orders, reaffirmation from the Assistant Secretary of Indian Affairs or federal court decisions.

The government prefers the administrative process because documentation is required, and it’s perceived as objective. But it’s difficult for tribes to collect all the documentation needed to apply and a lot of tribes cannot complete — or in some cases, even start — the process, given the time and expense involved.

Since 1978, 34 tribes have been denied acknowledgement, and 18 tribes approved. Currently, there are only six tribes under review to become recognized, and that includes two California tribes: the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation — from Yosemite Valley — and the Ahmah Mutsun Band of Ohlone Indians from the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Native American grassroots movement of the late 1960s inspired many tribes to seek recognition, and petitions to the government increased in the 1970s. As a result, the Department of Interior created the administrative process and the Office of Federal Acknowledgement to manage applications that first became effective on Oct. 2, 1978.

The first set of regulations, revised in 1994, required tribes to collect all sorts of historical and anthropological evidence to meet seven criteria that prove their continuous existence, activities and cohesion as a tribe from the 1800s to the present.

“In some cases, there’s thousands and thousands of documents,” Azocar said. “The process has gotten more and more rigorous, even though there is nothing that says that it necessarily has to meet a certain standard, but there is a precedent that has been set.”

Jordyn Gleaton / San Francisco Public Press

In 2015, the regulations were revised again, and the amount of evidence required was reduced. Now, tribes have to show only documentation from the early 1900s to the present day, but this is often still an overwhelming challenge. The goal of the revision was to make the process more transparent and flexible in recognition of the fact that all tribes were not homogenous. Even so, the administration still asked for evidence that in some cases was impossible to produce.

“The Office of Federal Acknowledgement suggested that it gather phone records of tribal members who had conversations with each other,” said Azocar, referencing the Little Shell Tribe in a passage in her book, News Media and the Indigenous Fight for Federal Recognition. “And I thought, that’s crazy. How would you actually be able to go about doing that?”

In addition, since tribes had no way to know they would need the records later, they didn’t always keep documentation.

To date, no tribe has been recognized through the new regulations introduced in 2015. Lee Fleming, director of the Office of Federal Acknowledgement within the Department of the Interior, declined to answer Azocar’s questions about the administrative process, and did not explain why the process took so long or how they hired staff to perform the reviews.

The government made documenting Native American tribal history challenging in multiple ways. The Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation, for example, had negotiated a treaty with U.S. in the 1850s, but the U.S. Congress did not ratify it. It was the peak of the Gold Rush, and the interests of white Californians were prioritized. The census also did not start counting Indians until 1850, and many tribes had already been displaced from their homelands.

“There were no records of Indians before 1815, so that is also a problem with getting historical documentation when tribes weren’t even part of the count of our country,” Azocar said.

And some of the evidence tribes are tasked with submitting was erased by racist laws. In Virginia, “You can’t trace your ancestry back past 1924,” Azocar said. A law called the Racial Integrity Act required anyone who was not white, including Native Americans, to be registered as “colored” on birth or marriage certificates.

Evidence collection can be costly, too. The Native American Rights Fund spent 29 years and more than 3,400 attorney hours on the federal recognition of the Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana, Azocar said. “The cost of that time was already in excess of $1 million.”

Even after all the expenditures, the tribe was not recognized through the federal acknowledgement process, but in an act of Congress as part of the National Defense Authorization Act in 2020.

“It’s really difficult, because often a tribe can’t do it itself,” Azocar said. “It has to hire historians, it has to hire anthropologists. And these often cost money unless somebody’s willing to do it for free.”

A fight for recognition

The application process requires tribes to meet seven criteria: that they have existed continuously over a historical period, that they constitute a unique and distinct community, that they have political authority over their tribal members, that they have an internal governing structure in place, that membership consists of individuals descended from a historical Indian tribe, that those members are not part of any other federally acknowledged tribe, and that the U.S. government has not forbidden or terminated recognition of the tribe.

Jordyn Gleaton / San Francisco Public Press

In 1982, after the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation notified the government that it intended to seek federal recognition, it had to undergo several rounds of documentation production and technical review. Two years after filing its letter of intent, the tribe submitted its initial documented petition prepared by anthropologists Lowell John Bean and Sylvia Brakke, who worked to change the depictions of California Indians. The tribe then spent 14 years gathering additional evidence.

In 1998, the tribe was ready. But the government was not. It was not until 2010 that the tribe was designated “active consideration” — meaning the government is ready to review the tribe’s application. At that point, the administration had one year to complete the review. The Interior Department filed 21 extensions, giving itself more than eight years to complete its initial evaluation.

“We’ve been put on hold now, all this time,” said Sandra Chapman, the tribe’s chairwoman. “We’re trying to get a meeting with Deb Haaland. We need to have her backing.” Haaland is the Secretary of the Interior, the first Indigenous woman to hold a Cabinet-level position.

In 2018, the Interior Department’s Office of Federal Acknowledgement published a preliminary finding denying recognition to the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation. The tribe did not meet the community criterion and more evidence needed to be submitted on the history, geography, culture and social organization of the group, the office said.

To better understand the decision, the tribe filed a Freedom of Information Act request for all correspondence and documents from the Office of Federal Acknowledgement relating to the decision-making process on its request. Four years later, the tribe is still waiting for a response.

The tribe has submitted about 200 years’ worth of evidence, dating back to the 1800s, as required by the 1994 regulations. The documentation would have been cut in half under the new regulations, but that would restart the application process.

The Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation has a federal acknowledgement committee and a membership committee that have worked to get its documentation compiled. “We have our genealogy, all documented,” Chapman said. “We are going to send that evidence to Washington, we’re going to overload them with all kinds of evidence, we’re going to give them more than they asked for and see what they say now.”

Tribe members have also received support from Yosemite National Park, which has an ongoing consultation relationship with seven tribes, including the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation, also known as the American Indian Council of Mariposa County.

“This relationship has existed for over 40 years,” a letter of support from the park for the tribe’s recognition said, noting that its “ancestral ties to Yosemite National Park have spanned multiple generations … and began prior to the establishment of the Park.” The U.S. Congress passed the first law protecting the Yosemite area in 1864 and created the park itself in 1890.

“We’re a strong community,” said Chapman, pointing to letters of support from local residents and the Board of Supervisors as well as the Park Service, which also welcomed a traditional village on the land. “How can you build a roundhouse on, you know, federal land? If you’re not a tribe?”

Azocar pointed to the tourism industry surrounding Yosemite National Park as a reason the government may be reluctant to grant the tribe recognition.

“If the tribe had further recognition, it would potentially have more power to have not just a lease, but have a stand to reclaim some of the territory,” she said, noting that “reclamation of territory is not necessarily in the interest of the federal government.”

The initial denial of recognition puts the tribe in phase two of the federal recognition process, giving members an opportunity to present additional evidence that they should be recognized. The tribe is working to rebut the denial and requesting public comment letters to aid in the effort. Comments close on Nov. 11, 2022.

If an application has been given a final decision, and federal acknowledgement is denied, the tribe cannot apply again. Tribes can seek alternative routes such as the courts or lobbying state senates to federally acknowledge them through public law, but these methods are just as expensive and difficult.

Some states offer tribes recognition, but it doesn’t come with federal benefits, like health and education assistance. But it can help with the federal recognition process to demonstrate a relationship over time with other governments, Azocar said.

“I am passionate that we become federally recognized,” Chapman said. “Our ancestors had wanted it. I remember my mom and dad saying they wanted to be recognized. It’s the recognition that you get that the government is saying, I know who you are.”

— Additional research and reporting contributed by Jordyn Gleaton

Jordyn Gleaton helped research and produced the graphics for this article. She is working with the San Francisco Public Press as a 2022 Dow Jones News Fund data journalism intern. Gleaton is entering her junior year at the University of California, Berkeley, where she is double majoring in political science and legal studies, and pursuing a human rights interdisciplinary minor.