[ad_1]

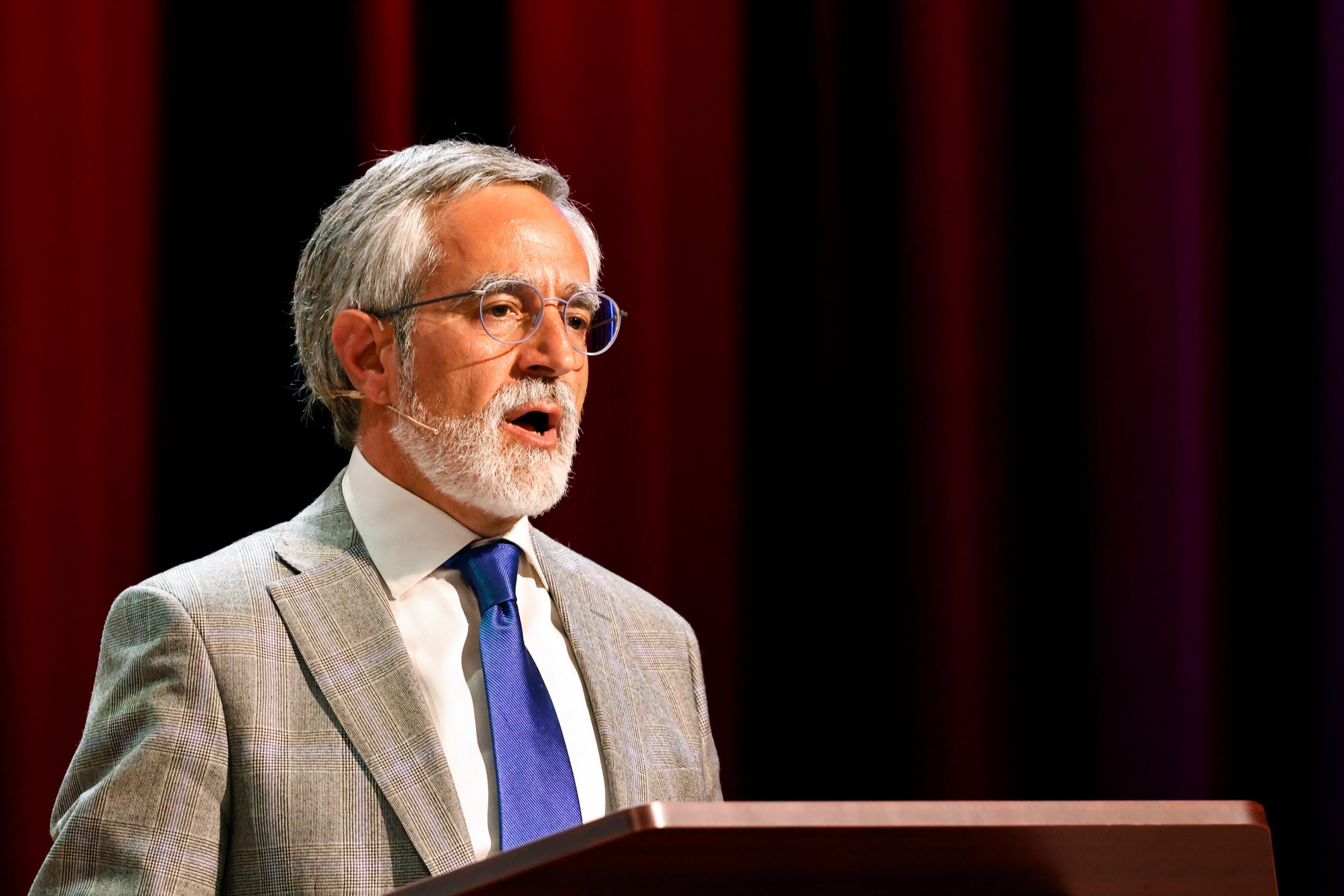

San Francisco Board of Supervisors president, mayoral candidate, and wildly prolific legislator Aaron Peskin lost the election to Daniel Lurie, a wealthy candidate with zero legislative experience.

But his three main ballot initiatives are winning and will, barring unforeseen lunacy, pass into legislation. Here’s the story of how they made it.

Prop. C

Creating a position for an inspector general with the power to investigate government and city contractor fraud, waste, abuse or misconduct would seem like a tough measure to oppose. It didn’t require any new funding, every single member of the Board of Supervisors voted to put it on the ballot, and corruption scandals have been breaking at a steady clip for years. But GrowSF, TogetherSF Action and the San Francisco Democratic Party all came out against it.

It got 60 percent of the preliminary vote anyway. Partly that’s because Peskin did a good job getting the word out, says Jim Stearns, a consultant to many progressive campaigns including Peskin’s mayoral bid. Peskin is enough of a policy wonk that he had more plans for improving the functioning of city government than he could cram into any one appearance. His six-point plan to reduce homelessness was more like an 11 million point plan. But he brought up the inspector general every time he made a campaign speech.

Their opposition to Prop. C speaks to a larger problem for Together SF, Grow SF, and the other groups that have been spending big on local elections, says Stearns. When they issue endorsements they’re trying to mimic local progressive groups whose endorsements have real sway — like the Harvey Milk Democratic Club. But unlike those groups, they don’t have a voting membership, and the process by which they make endorsements isn’t transparent and feels highly personal and idiosyncratic. Why paper the city with ads complaining about city corruption in support of Prop. D, but not support Prop. C? At any rate, says Stearns, the voters didn’t buy it — Prop. C is passing with ease, in spite of minimal funding.

Prop. E

Prop. E was created by Peskin’s office in response to Prop. D — a ballot measure, created and lavishly funded by Together SF, that would have given the mayor power to eliminate entire advisory boards and commissions as well as weakening civilian oversight of the Police Commission, under the guise of making city government more efficient. Michael Moritz, the local billionaire who poured at least $3.2 million of his money into Prop. D, described the measure as “the greatest gift anybody has given to a mayor in the recent history of San Francisco.”

Like Prop. D, Proposition E also proposed to streamline the city’s admittedly commission-heavy structure — but via an independent blue-ribbon panel that will make any changes within a system of public hearings. Supporters of Prop. E. had less than 1 percent of the money that Prop. D did, says Doug Engmann, former president of the Planning Commission. What they had instead was a network of good government types who were horrified at the potential consequences of Prop. D and who began working together to place op-eds in local publications explaining the risks posed by it. “We spread the network rapidly,” says Engmann. “You can see it in the ballot handbook. Within a month, we had more endorsements from prestigious organizations than they did.” No less than the San Francisco Bar Association came out against Prop. D.

The No on D Yes on E crowd was also aided by mayoral candidate Mark Farrell’s decision to create a PAC in support of Prop. D and commingle its funds with his mayoral committee — which resulted in a $108,000 ethics penalty announced the day before the election. That was the coup de grâce to a long slide downward in public opinion and, as Farrell struggled, he took Prop. D down with him. Think about it, says Engmannn: If you got 16 flyers from Mark Farrell saying “Vote Yes on D” and every day you read more about Mark Farrell and his ethics violations, Prop. D does not look good. “He did all of the advertising for us!” says Engmann.

Prop. E remains a close call — it is receiving a bit over 51 percent of the early vote, but its margins are growing with each subsequent ballot drop. But 55 percent of voters have said No on Prop. D, and it continues to drop. It was a new milestone for Stearns. ”I’ve never been out-spent $8 million to $80,000 and won,” he says, laughing. (The amount spent in support of D is, at last count, $9,522,242).

Prop. G

This one was classic Peskin legislation — a tweak to the unintended consequences of encouraging housing nonprofits to buy SRO hotels full of elderly tenants to create permanently affordable housing. The problem was, many of those tenants were so poor that the nonprofits couldn’t afford to run or maintain the buildings on the rents they were paying. Prop. G creates a fund to help offset those costs. Together SF and Grow SF opposed this measure too, but it didn’t hold much sway against the legions of housing groups, anti-poverty groups, and churches that supported it. It got over 56 percent of the vote.

So how is it that Peskin’s measures won but the guy didn’t? Stearns was aware early on that the challenge with Peskin’s mayoral run was years of negative campaigning about Peskin the person, which kicked into gear the first time he was elected to the Board of Supervisors in 2000. In those days, that campaigning came from old school business lobbying groups like The Committee on Jobs. Today, it’s Neighbors for a Better San Francisco and Together SF, which openly pursued an “anyone but Peskin” strategy even as they struggled over who they wanted to see in Room 200.

A candidate with Peskin’s baked-in negatives wasn’t going to receive enough No. 2 votes to overcome Mayor London Breed. And it was difficult for a candidate raising money in $500 increments to make headway in the free-spending atmosphere created by mayor-elect Daniel Lurie, who put some $16 million into his campaign. Peskin, for his part, led in small-dollar donations.

These were not factors in Peskin’s many victorious runs for supervisor. Negative campaigning couldn’t sink Peskin in District 3, says Stearns. Too many people there knew him — or knew people who did. But it’s tough to scale up the kind of voter outreach a grassroots campaign can do in North Beach and Chinatown — two of the most densely populated, closely-knit, pedestrian-oriented neighborhoods — to a city of over 800,000.

Peskin’s mayoral bid could not overcome the political headwinds. But his policies sailed through, regardless. “The city likes Aaron,” says Stearns. “Aaron the legislator.”

[ad_2]

Source: missionlocal.org